Open Source: Where the common man presides

Project idea

In the last hundred and thirty years, the degree and pace of change in architecture is hard to comprehend. On one hand, revolutionary innovation unimaginable even a decade ago has become the new normal with the rise of the internet. On the other, the urban fabric’s defiant persistence and apparent vigour– creatively, logistically, politically – is evident. The city pleads for a response from the architectural practice.

In Delhi, mounting pressures on land as a resource and consequent problems with urban transportation and environmental degradation create the need to densify existing precincts of the city. In July 2016, the Union Cabinet, Government of India approved the redevelopment of General Pool Residential Accommodation (GPRA) colonies: largest of which is Sarojini Nagar. However, several issues regarding densification arise immediately: In addition to the recent uproar about felling of mature trees at the Sarojini Nagar site, the scale and intensity of such developments give rise to apprehensions about the visions behind these developments. It clearly indicates a need to tread softly and redefine the architectural design paradigm.

This project bridges the gap by adopting a novel approach to architectural design development: Open Source. The principle of Open Source- to create rapidly adaptable designs through exhaustive analysis of user aspiration and behavioural changes- is leveraged to create a people-centric project. At all the 4 scales involved in project development, user feedback leads to the design vision.

Project description

The overall masterplan, developed after feedback from 73 residents, is focussed on aligning with the vision of the city. The major socio-cultural nodes i.e. Sarojini Nagar Market, Pilanji urban village and the social infrastructure are retained to preserve the identity and the rest is turned into a pedestrian-paradise. The mass-transit system is kept as the epicentre and the built-mass is organized as per the lush-green tree cover to create a carbon-sink for the city. Jogging and cycling paths meander through the interstices of the built mass.

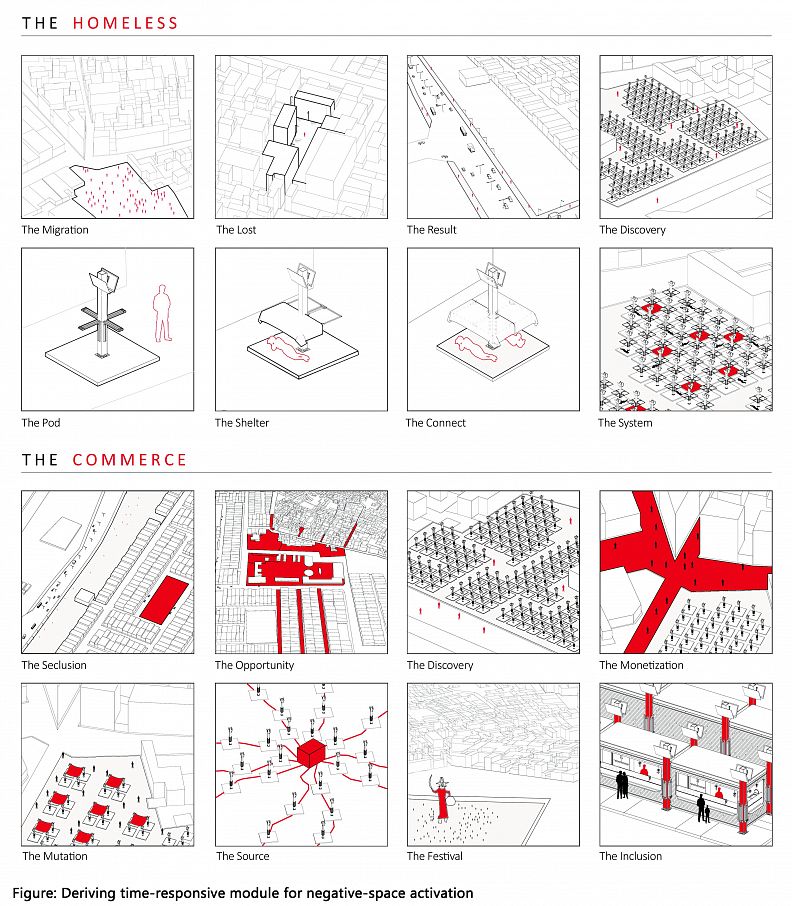

At the precinct scale, an inclusive urban fabric operates. Six major anchors- private micro apartment, social condenser, commercial cluster, liquid urban space, cathemeral node and cross-programmed amenity- are identified by surveying for people’s requirements. Their equitable placement creates a self-sustaining social network that generates socio-cultural activation of the fabric, across age and class hierarchies.

With the urban fabric in-place, the focus turns to developing the program and tectonics. The programmes to be included in the project are re-defined for their present-day usability by interpreting data obtained from tracking of people’s behavioural patterns, through the day. This movement-event-program analysis creates volumes and adjacencies that promotes rapidly changing spatial occupation throughout the day. The resident sleeps, the streets and spaces do not.

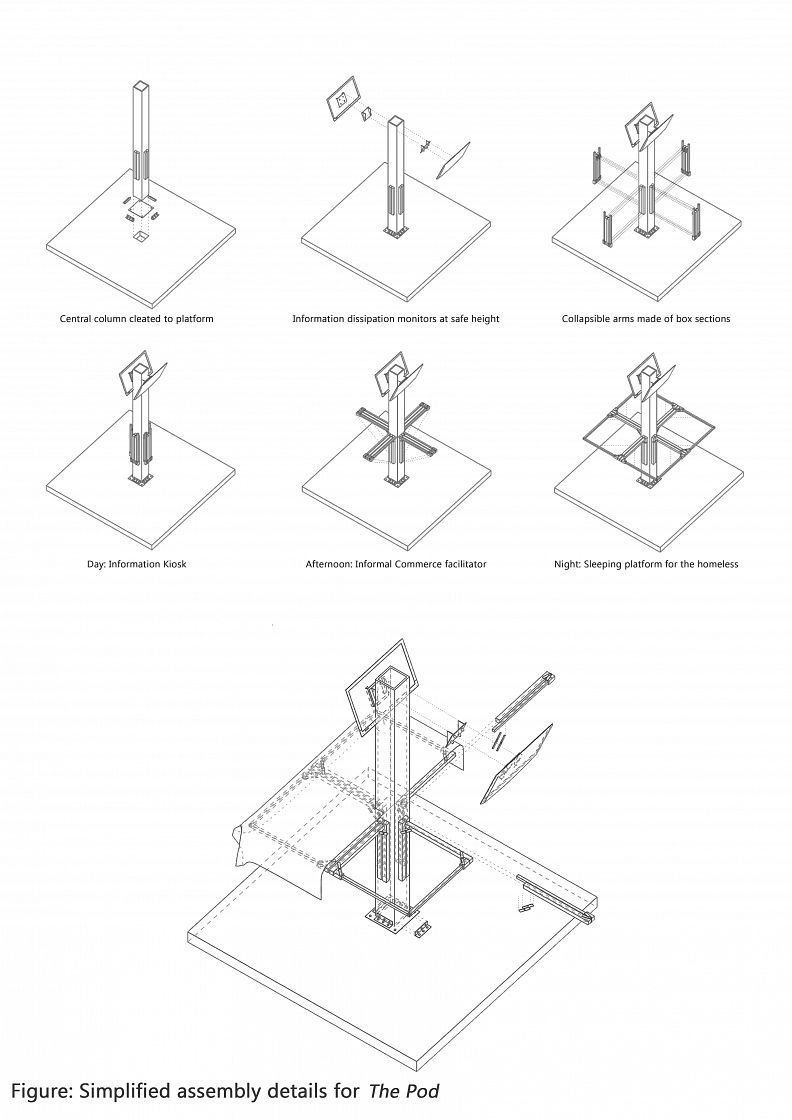

At the micro level, the spaces generated in the tectonics are further optimized by incorporation of modular operability. A simulation is carried out to check the usage efficiency of the developed spaces that reveals the specific spatial volumes facing failure. For these specific volumes, modular logistics are developed to provide enhanced adaptability and even dismantling possibilities.

All elements developed in the proposed design-from Liquid Urban Spaces at the macro scale to the 3-way Pod system at the micro level-are designed to serve, not lead. An architecture so versatile, accommodative, boundless and most importantly morphable gives the power back to the citizens. In Delhi, a city drugged on new spaces for real estate and more inches of shining glass on heat absorbing concrete, is an abode where the common man presides.

Technical information

As above